A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock () or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Ozone is present only in small amounts in Earth's atmosphere. Nevertheless, it is vital to human well-being and ecosystem health.

Most ozone resides in the upper part of the atmosphere. This region, called the stratosphere, is more than 10 kilometers (6 miles) above Earth's surface. There, about 90% of atmospheric ozone is contained in the "ozone layer," which shields us from harmful ultraviolet radiation from the Sun.

It was discovered in the mid-1970s that some human-produced chemicals could lead to depletion of the ozone layer. The resulting increase in ultraviolet radiation at Earth's surface would likely increase the incidences of skin cancer and eye cataracts, and also adversely affect plants, crops, and ocean plankton.

Following the discovery of this environmental issue, researchers sought a better understanding of this threat to the ozone layer. Monitoring stations showed that the abundances of the ozone-depleting substances (ODSs) were steadily increasing in the atmosphere. These trends were linked to growing production and use of chemicals like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) for refrigeration and air conditioning, foam blowing, and industrial cleaning. Measurements in the laboratory and in the atmosphere characterized the chemical reactions that were involved in ozone destruction. Computer models of the atmosphere employing this information were used to predict how much ozone depletion was occurring and how much more might occur in the future.

Observations of the ozone layer showed that depletion was indeed occurring. The most severe and most surprising ozone loss was discovered to be recurring in springtime over Antarctica. The loss in this region is commonly called the "ozone hole" because the ozone depletion is so large and localized. A thinning of the ozone layer also has been observed over other regions of the globe, such as the Arctic and northern and southern midlatitudes.

The work of many scientists throughout the world has provided a basis for building a broad and solid scientific understanding of the ozone depletion process. With this understanding, we know that ozone depletion is indeed occurring and why. Most important, we know that if the most potent ODSs were to continue to be emitted and increase in the atmosphere, the result would be more depletion of the ozone layer.

In response to the prospect of increasing ozone depletion, the governments of the world crafted the 1987 United Nations Montreal Protocol as an international means to address this global issue. As a result of the broad compliance with the Protocol and its Amendments and Adjustments and, of great significance, industry's development of "ozone-friendly" substitutes for the now-controlled chemicals, the total global accumulation of ODSs has slowed and begun to decrease. In response, global ozone depletion is no longer increasing. Now, with continued compliance, we expect substantial recovery of the ozone layer by the late 21st century. The day the Montreal Protocol was agreed upon, 16 September, is now celebrated as the International Day for the Preservation of the Ozone Layer.

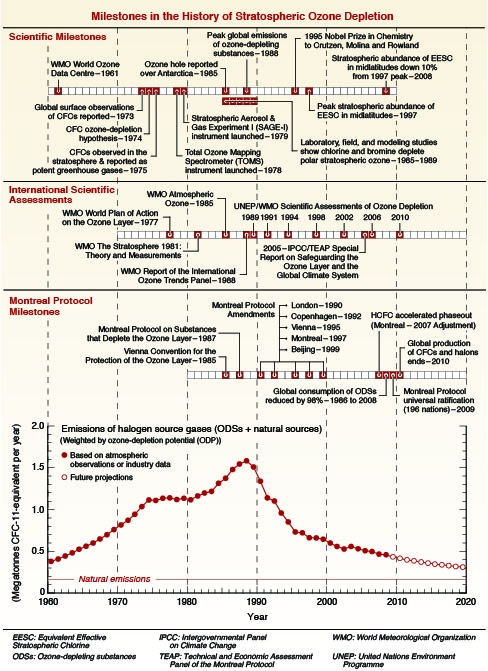

This is a story of notable achievements: discovery, understanding, decisions, actions, and verification. It is a story written by many: scientists, technologists, economists, legal experts, and policymakers, in which continuous dialogue has been a key ingredient. A timeline of milestones associated with stratospheric ozone depletion is illustrated in Figure Q0-1. The milestones relate to stratospheric ozone science, international scientific assessments, and the Montreal Protocol.

To help maintain a broad understanding of the relationship between ozone depletion, ODSs, and the Montreal Protocol, this component of the Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2010 presents 20 questions and answers about the often-complex science of ozone depletion. Most questions and answers are updates of those presented in previous Ozone Assessments, while others have been added or expanded to address newly emerging issues. The questions address the nature of atmospheric ozone, the chemicals that cause ozone depletion, how global and polar ozone depletion occur, the success of the Montreal Protocol, and what could lie ahead for the ozone layer. Computer models project that the influence on global ozone of greenhouse gases and changes in climate will grow significantly in the coming decades and exceed the importance of ODSs in most atmospheric regions by the end of this century. Ozone and climate are indirectly linked because both ODSs and their substitutes contribute to climate change. A brief answer to each question is first given in italics; an expanded answer then follows. The answers are based on the information presented in the 2010 and earlier Assessment reports as well as other international scientific assessments. These reports and the answers provided here were prepared and reviewed by a large international group of scientists1.

This timeline highlights milestones related to the history of ozone depletion. Events represent the occurrence of important scientific findings, the completion of international scientific assessments, and highlights of the Montreal Protocol. The graph shows the history and near future of annual total emissions of ozone-depleting substances (ODSs) combined with natural emissions of halogen source gases. ODSs are halogen source gases controlled under the Montreal Protocol. The emissions, when weighted by their potential to destroy ozone, peaked near 1990 after several decades of steady increases (see Q19 ). Between 1990 and the present, emissions have decreased substantially as a result of the Montreal Protocol and its subsequent Amendments and Adjustments coming into force (see Q15 ). The Protocol began with the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer in 1985. The provisions of the Protocol and its Amendments and Adjustments decisions have depended on information embodied in international scientific assessments of ozone depletion that have been produced periodically since 1989 under the auspices of UNEP and WMO. Atmospheric observations of ozone, CFCs, and other ODSs have increased substantially since the early 1970s. For example, the SAGE and TOMS satellite instruments have provided essential global views of stratospheric ozone for several decades. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995 was awarded for research that identified the threat to ozone posed by CFCs and that described key reactive processes in the stratosphere. By 2008, stratospheric chlorine abundances in the stratosphere were 10% lower than their peak values reached in the late 1990s and were continuing to decrease. January 2010 marked the end of global production of CFCs and halons under the Protocol. (A megatonne = 1 billion (109) kilograms.)

EESC: Equivalent effective stratospheric chlorine

ODS: Ozone-depleting substance

WMO: World Meteorological Organization

IPCC: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

TEAP: Technology and Economic Assessment Panel of the Montreal Protocol

UNEP: United Nations Environment Programme

[1] The update of this component of the Assessment was discussed by the 74 scientists who attended the Panel Review Meeting for the 2010 Ozone Assessment (Les Diablerets, Switzerland, 28 June-2 July 2010). In addition, subsequent contributions, reviews, or comments were provided by the following individuals: Ross J. Salawitch (Special Recognition), Stephen A. Montzka (Special Recognition), Stephen O. Andersen (Special Recognition), Pieter J. Aucamp, Alkiviadis F. Bais, Peter F. Bernath, Gregory E. Bodeker, Janet F. Bornman, Geir O. Braathen, Peter Braesicke, Irene Cionni, Martin Dameris, John S. Daniel, Susana B. Diaz, Ellsworth G. Dutton, James W. Elkins, Christine A. Ennis, Veronika Eyring, Vitali E. Fioletov, Marvin A. Geller, Sophie Godin-Beekmann, Malcolm K.W. Ko, Kirstin Krüger, Lambert Kuijpers, Michael J. Kurylo, Igor Larin, Gloria L. Manney, C. Thomas McElroy, Rolf Müller, Eric R. Nash, Paul A. Newman, Samuel J. Oltmans, Nigel D. Paul, Judith Perlwitz, Jean-Pierre Pommereau, Claire E. Reeves, Stefan Reimann, Alan Robock, Michelle L. Santee, Dian J. Seidel, Theodore G. Shepherd, Peter Simmonds, Anne K. Smith, Richard S. Stolarski, Matthew B. Tully, Guus J.M. Velders, Elizabeth C. Weatherhead, Ann R. Webb, Ray F. Weiss, and Durwood Zaelke.