A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock () or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

The springtime Antarctic ozone hole is a new phenomenon that appeared in the early 1980s.

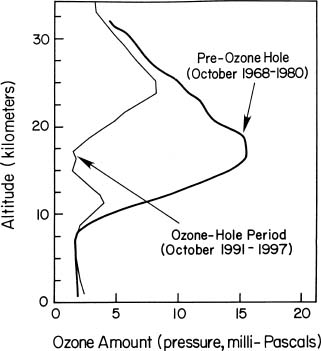

The observed average amount of ozone during September, October, and November over the British Antarctic Survey station at Halley, Antarctica, first revealed notable decreases in the early 1980s, compared with the preceding data obtained starting in 1957. The ozone hole is formed each year when there is a sharp decline (currently up to 60%) in the total ozone over most of Antarctica for a period of about three months (September-November) during spring in the Southern Hemisphere. Late-summer (January-March) ozone amounts show no such sharp decline in the 1980s and 1990s. Observations from three other stations in Antarctica and from satellite-based instruments reveal similar decreases in springtime amounts of ozone overhead. Balloonborne ozone instruments show dramatic changes in the way ozone is distributed with altitude. As the figure below from the Syowa site shows, almost all of the ozone is now depleted at some altitudes as the ozone hole forms each springtime, compared to the normal ozone profile that existed before 1980. As explained in an earlier question (page 24), the ozone hole has been shown to result from destruction of stratospheric ozone by gases containing chlorine and bromine, whose sources are mainly human-produced halocarbon gases.

Before the stratosphere was affected by human-produced chlorine and bromine, the naturally occurring springtime ozone levels over Antarctica were about 30-40% lower than springtime ozone levels over the Arctic. This natural difference between Antarctic and Arctic conditions was first observed in the late 1950s by Dobson. It stems from the exceptionally cold temperatures and different winter wind patterns within the Antarctic stratosphere as compared with the Arctic. This is not at all the same phenomenon as the marked downward trend in ozone over Antarctica in recent years.

Changes in stratospheric meteorology cannot explain the ozone hole. Measurements show that wintertime Antarctic stratospheric temperatures of past decades had not changed prior to the development of the ozone hole each September. Ground, aircraft, and satellite measurements have provided, in contrast, clear evidence of the importance of the chemistry of chlorine and bromine originating from human-made compounds in depleting Antarctic ozone in recent years.