A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock () or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

16 October 2019

adapted from the story by CIRES Communications

Global airborne mission finds a belt of particle formation is brightening clouds.

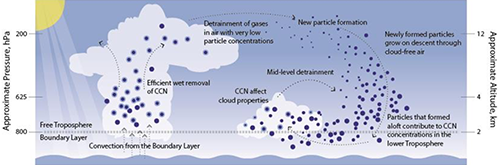

When clouds loft tropical air masses higher in the atmosphere, that air can carry up gases that form into tiny particles, starting a process that may end up brightening lower-level clouds, according to a CIRES-led study published in Nature. Clouds alter Earth's radiative balance, and ultimately climate, depending on how bright they are. And the new paper describes a process that may occur over 40 percent of the Earth's surface, which may mean today's climate models underestimate the cooling impact of some clouds.

"Understanding how these particles form and contribute to cloud properties in the tropics will help us better represent clouds in climate models and improve those models," said Christina Williamson, a CIRES scientist working in CSD and the paper's lead author.

The research team mapped out how these particles form using measurements from one of the largest and longest airborne studies of the atmosphere, a field campaign that spanned the Arctic to the Antarctic over a three-year period.

Williamson and her colleagues, from CIRES, CU Boulder, NOAA and other institutions, took global measurements of aerosol particles as part of the Atmospheric Tomography Mission (ATom). During ATom, a fully instrumented NASA DC-8 aircraft flew four pole-to-pole deployments – each one consisting of many flights over a 26-day period – over the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans in every season. The plane flew from near sea level to an altitude of about 12 km, continuously measuring greenhouse gases, other trace gases and aerosols.

"ATom is a flying chemistry lab," Williamson said. "Our instruments allowed us to characterize aerosol particles and their distribution in the atmosphere." The researchers found that gases transported to high altitudes by deep, convective clouds in the tropics formed large numbers of very small aerosol particles, a process called gas-to-particle conversion.

Outside the clouds, the air descended toward the surface and those particles grew as gases condensed onto some particles and others stuck together to form fewer, bigger particles. Eventually, some of the particles became large enough to influence cloud properties in the lower troposphere.

In their study, the researchers showed that these particles brightened clouds in the tropics. "That's important since brighter clouds reflect more energy from the sun back to space," Williamson said.

The team observed this particle formation in the tropics over both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, and their models suggest a global-scale band of new particle formation covering about 40 percent of the Earth's surface.

In places with cleaner air where fewer particles exist from other sources, the effect of aerosol particle formation on clouds is larger. "And we measured in more remote, cleaner locations during the ATom field campaign," Williamson said.

Exactly how aerosols and clouds affect radiation is a big source of uncertainty in climate models. "We want to properly represent clouds in climate models," said Williamson. "Observations like the ones in this study will help us better constrain aerosols and clouds in our models and can direct model improvements."

Williamson, C.J., A. Kupc, D. Axisa, K.R. Bilsback, T. Bui, P. Campuzano-Jost, M. Dollner, K.D. Froyd, A.L. Hodshire, J.L. Jimenez, J.K. Kodros, G. Luo, D.M. Murphy, B.A. Nault, E.A. Ray, B.B. Weinzierl, J.C. Wilson, F. Yu, P. Yu, J.R. Pierce, and C.A. Brock, A large source of cloud condensation nuclei from new particle formation in the tropics, Nature, doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1638-9, 2019.

Cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) can affect cloud properties and therefore Earth's radiative balance. New particle formation (NPF) from condensable vapours in the free troposphere has been suggested to contribute to CCN, especially in remote, pristine atmospheric regions, but direct evidence is sparse, and the magnitude of this contribution is uncertain. Here we use in situ aircraft measurements of vertical profiles of aerosol size distributions to present a global-scale survey of NPF occurrence. We observe intense NPF at high altitudes in tropical convective regions over both Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Together with the results of chemical-transport models, our findings indicate that NPF persists at all longitudes as a global-scale band in the tropical upper troposphere, covering about 40 per cent of Earth's surface. Furthermore, we find that this NPF in the tropical upper troposphere is a globally important source of CCN in the lower troposphere, where CCN can affect cloud properties. Our findings suggest that the production of CCN as new particles descend towards the surface is not adequately captured in global models, which tend to underestimate both the magnitude of tropical upper tropospheric NPF and the subsequent growth of new particles to CCN sizes.