A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock () or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

13 March 2025

adapted from the story by NOAA Communications

As the adoption of cleaner-burning engines and electric vehicles drives fossil fuel emissions lower, scientists have discovered that a surprising pollution source is playing a significant role in cooking up ozone in the air over Los Angeles.

According to new research from NOAA, the potent and often pungent volatile organic compounds (VOCs) given off from cooking food are now responsible for over a quarter of the ozone production from VOCs generated by human activity in the LA basin. This is roughly equal to the amount of ozone produced by VOCs from on-road and off-road motor vehicles.

The new study, published in Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, takes a more complete look at the mix of VOCs in urban air by adding chemical compounds specific to cooking emissions to an air quality model set up to replicate the conditions in and around Los Angeles.

"We knew from our research that chemical compounds from cooking can make up an important fraction of VOCs present in urban air, but they were not well represented in inventories or included in air quality models," said lead author Chelsea Stockwell, a research chemist at NOAA CSL. "Given the known chemical reactivity of these compounds, their omission from air quality models may be a blind spot when it comes to urban ozone production."

VOCs are one of the two ingredients necessary for creating ground-level ozone, an EPA-regulated air pollutant that in high concentrations is toxic to humans, animals and plants. Ozone is formed in the atmosphere when VOCs undergo a series of photochemical reactions with nitrogen oxides or NOx, which is primarily generated by vehicle exhaust.

Over the past several decades, efforts to reduce ozone pollution by controlling emissions from the transportation sector substantially improved air quality across the country. But in recent years, the trend toward cleaner air has leveled off, and some locations have seen moderate increases in maximum daily ozone. This has motivated scientists to reexamine today's modern mix of air pollutants and their sources to assess where and how further air quality improvements could be realized.

In the past 10 years, several major research campaigns have targeted Los Angeles, which has some of the worst air quality in the country.

The incorporation of cooking emissions into an air quality model by a research team of NOAA and CIRES scientists was prompted by results from the SUNVEx 2021 field experiment by CSL around LA and Las Vegas. Analysis of air sampling revealed that VOCs unique to cooking were enhanced in downtown areas where restaurants were most abundant. Twenty-one percent of human-generated VOCs sampled in Las Vegas were chemical compounds derived from cooking oils and fats. The VOCs attributed to the cooking sector are not reflected in the EPA's National Emissions Inventory.

Because the chemical reactions that create ozone are complex, an air quality model is needed to estimate the actual amount of ozone generated by these compounds. Fully accounting for the different types and sources of VOCs in models, including those from cooking, is critical for correctly understanding a particular city's ozone production.

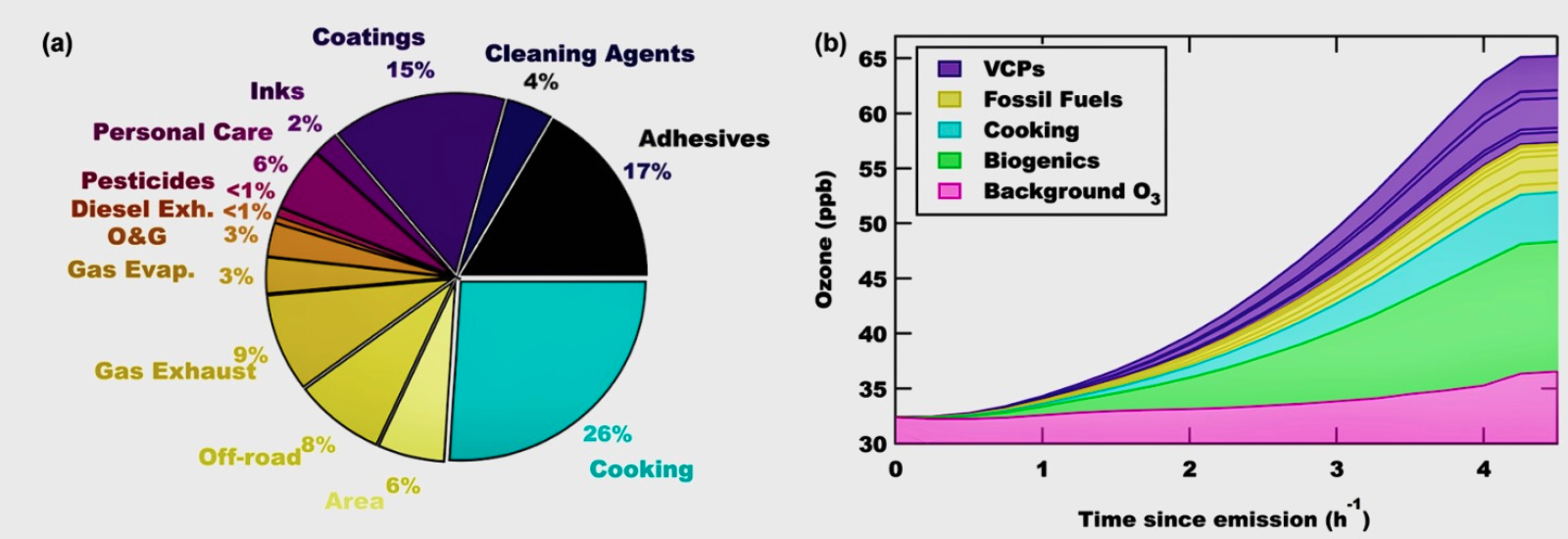

According to this new research, about half of the ozone produced locally from VOCs in the LA basin (in other words, above the typical background value) arises from natural VOC sources such as trees and foliage and ozone in air flowing into the city. The other half is generated locally by human activity.

The largest source of human-produced VOCs leading to ozone pollution in the LA basin are volatile chemical products, or VCPs. These are a class of consumer products that include paints, adhesives, pesticides, and personal care products, another category of under-appreciated pollutants that CSL scientists had previously explored. Chemicals emitted by these products during their normal use contribute roughly 45% of the ozone pollution generated by human activities. Cooking emissions contribute 26%. Fossil fuel sources, primarily made up of on-road and off-road emissions from diesel and gas engines contribute 29%, respectively.

Even though cooking emissions are a lesser contributor to LA's total ozone burden, they're still important, said Stockwell.

"Investigating these emissions is necessary to understand our changing urban VOC mixture, and for developing strategies that could be used to reduce ozone pollution," Stockwell said. "Ultimately, more research will be needed to get a better grasp on whether cooking odors affect ozone pollution in other cities."

Stockwell, C.E., M.M. Coggon, R.H. Schwantes, C. Harkins, B. Verreyken, C. Lyu, Q. Zhu, L. Xu, J.B. Gilman, A. Lamplugh, J. Peischl, M.A. Robinson, P.R. Veres, M. Li, A.W. Rollins, K. Zuraski, S. Baidar, S. Liu, T. Kuwayama, S.S. Brown, B.C. McDonald, and C. Warneke, Urban ozone formation and sensitivities to volatile chemical products, cooking emissions, and NOx upwind of and within two Los Angeles Basin cities, Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, doi:10.5194/acp-25-1121-2025, 2025.

Volatile chemical products (VCPs) and other non-traditional anthropogenic sources, such as cooking, contribute substantially to the volatile organic compound (VOC) budget in urban areas, but their impact on ozone formation is less certain. This study employs Lagrangian box modeling and sensitivity analyses to evaluate ozone response to sector-specific VOC and nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions in two Los Angeles (LA) Basin cities during the summer of 2021. The model simulated the photochemical processing and transport of temporally and spatially gridded emissions from the FIVE-VCP-NEI17NRT inventory and accurately simulates the variability and magnitude of O3, NOx, and speciated VOCs in Pasadena, CA. VOC sensitivity analyses show that anthropogenic VOCs (AVOC) enhance the mean daily maximum 8 h average ozone in Pasadena by 13 ppb, whereas biogenic VOCs (BVOCs) contribute 9.4 ppb. Of the ozone influenced by AVOCs, VCPs represent the largest fraction at 45%, while cooking and fossil fuel VOCs are comparable at 26% and 29%, respectively. NOx sensitivity analyses along trajectory paths indicate that the photochemical regime of ozone varies spatially and temporally. The modeled ozone response is primarily NOx-saturated across the dense urban core and during peak ozone production in Pasadena. Lowering the inventory emissions of NOx by 25% moves Pasadena to NOx-limited chemistry during afternoon hours and shrinks the spatial extent of NOx saturation towards downtown LA. Further sensitivity analyses show that using VOCs represented by a separate state inventory requires steeper NOx reductions to transition to NOx sensitivity, further suggesting that accurately representing VOC reactivity in inventories is critical to determining the effectiveness of future NOx reduction policies.